…’The Arnolfini Wedding’ by Jan Van Eyck now hangs in the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery on the first floor. I first came across it when studying History of Art many years ago.

…’The Arnolfini Wedding’ by Jan Van Eyck now hangs in the Sainsbury wing of the National Gallery on the first floor. I first came across it when studying History of Art many years ago.

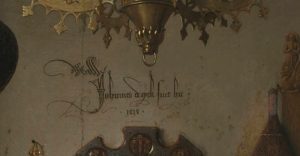

It was painted, in oil on an oak panel, in Bruges during 1434 and it is now thought to be of Giovanni di Nicholao Arnolfini and his wife. Arnolfini was a scion of a successful family of merchants from Lucca in northern Italy and was working in their Bruges business. When I studied it I was taught that it was a formally commissioned marriage portrait, painted, full of the symbolism of hoped-for marital bliss and fecundity, on the occasion of their wedding or of their formal betrothal. The art historian Helen Gardner described it thus – ‘Almost every object depicted is in some way symbolic of the holiness of matrimony. The persons themselves, hand in hand, take the marriage vows.’ ( Art Through the Ages )

Said symbolism included the little dog at the front of the painting, signifying fidelity, the oranges on the  window sill, signifying purity ( fruit from before the Fall ). There is a brush, signifying chastity and the domestic and a set of rock crystal prayer-beads, a common engagement present from grooms to brides at that time. There is a super-abundance of iconography.

window sill, signifying purity ( fruit from before the Fall ). There is a brush, signifying chastity and the domestic and a set of rock crystal prayer-beads, a common engagement present from grooms to brides at that time. There is a super-abundance of iconography.

The accoutrements of the couple’s surroundings, chandelier, seat-chest, curtained bed, are all indicators of preparation for and eventual consummation of their alliance. And its result, an heir for the family. Prospective marriage involved a long drawn-out negotiation in 15th century Italy or the Low Countries and well to do young women would be collecting their ‘bottom drawer’ ( a concept now completely redundant, at least as regards things ) from an early age.

Since my student days the art world has changed its view ( and there is still some dispute ). For some time the painting was known simply as ‘Portrait’, as the identity of the two people in it was disputed. Now, however, it is thought that the painting is of Giovanni di Nicholao Arnolfini and his first wife Constanza Trenta, not his cousin Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his wife, as  was previously thought. There isn’t total agreement, but many art historians now believe that the painting, far from being formally commissioned, was painted by Van Eyck for Giovanni because he was his friend.

was previously thought. There isn’t total agreement, but many art historians now believe that the painting, far from being formally commissioned, was painted by Van Eyck for Giovanni because he was his friend.

Constanza died in 1433, before the painting was finished, how we do not know. This means that one person in the Portrait is alive and one dead, which reflects the state of the chandelier, which has one candle – the one above Giovanni – alight and one snuffed out – the one above Constanza. Whereas I was taught that the single lighted candle represented the ‘eye of God’, watching over the formal event. The new interpretation makes much more sense.

There are still two major mysteries in the painting ( quite aside from Constanza’s fate ). Who are the people reflected in the convex mirror and is the  woman pregnant?

woman pregnant?

The mirror is a triumph of the painter’s art. It is painted as larger than technology then allowed and is highly decorated ( you need to look closely to find the inset pictures of The Passion of Christ around the mirror, but if you do, you will see that all the images of death lie on the right hand side, the side on which the woman is standing ). The image within the mirror is the reverse of that of the painting, showing the subjects’ backs and two people standing beyond them. One is thought to be Van Eyck, the painter, though it does not show him at his easel, as ‘Las Meninas‘ does Velasquez. The other is unknown. In the old theory of the betrothal, these were assumed to be witnesses and the mirror itself another ‘eye of God’.

The woman, let us assume she is Constanza, looks pregnant. Her form is distended and she rests her hand upon what appears to be her grown belly. Yet art historians say that she is not, she is wearing a ‘stomacher’ a fashion of the day, which gave women the appearance of much longed for gravidity. This is what the National Gallery notes to the picture say, placing emphasis on the cloth drawn up to and falling from her shape ( the Arnolfini’s were cloth importers ). The stomacher is a sort of physical manifestation of wishful thinking.

The woman, let us assume she is Constanza, looks pregnant. Her form is distended and she rests her hand upon what appears to be her grown belly. Yet art historians say that she is not, she is wearing a ‘stomacher’ a fashion of the day, which gave women the appearance of much longed for gravidity. This is what the National Gallery notes to the picture say, placing emphasis on the cloth drawn up to and falling from her shape ( the Arnolfini’s were cloth importers ). The stomacher is a sort of physical manifestation of wishful thinking.

I prefer the more obvious conclusion, though, I acknowledge, it is unsupported by any scholarly evidence, that Constanza is indeed pregnant. We don’t know how she died, but it could have been in childbirth, which was common ( though this is a supposition on my part ). If true, this would give the painting a poignancy that no amount of iconography or symbolism can equal. I prefer this story, as more romantic, in which the painting becomes an ‘In memoriam’, all the more affecting because it was probably begun, by the couple’s friend, as a celebration. It could easily be true.

One further small irreverence. When I last stood before this painting a man, middle-aged, bespectacled, came and stood beside me, peering intently at the male figure. When he stood back I gave him a quizzical look, hoping that he might explain his interest. He smiled, his expression sheepish, and said, ‘Vladimir Putin, he looks just like Vladimir Putin.’ Now I have to look at the painting again!

If you enjoyed reading this article you may also enjoy Art Eric Ravilious Frank Auerbach

For more about Jan van Eyck see Artsy

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts