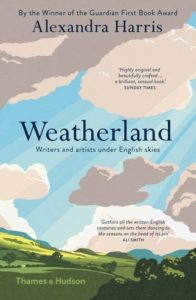

I promised that I would not blog about the weather – climate change or spectacular climactic events, yes, ordinary weather, no ( see Storm Warning ). I am, however, thoroughly enjoying reading about the weather, or rather the impact it has had, over time, on English thought, letters and literature in Alexandra Harris’s ‘Weatherland‘ ( Thames & Hudson, July 2016 ).

I promised that I would not blog about the weather – climate change or spectacular climactic events, yes, ordinary weather, no ( see Storm Warning ). I am, however, thoroughly enjoying reading about the weather, or rather the impact it has had, over time, on English thought, letters and literature in Alexandra Harris’s ‘Weatherland‘ ( Thames & Hudson, July 2016 ).

Winner, in 2011 of the Guardian First Book Award and the Somerset Maugham Award with ‘Romantic Moderns‘, Harris now teaches English Lit at Liverpool University. ‘Weatherland‘ is her second book. It begins with the Romans and winter, as depicted in Roman floor mosaics at Bignor and Chedworth and procedes through post-Roman Britain to the Anglo Saxons and Normans into the Middle Ages. It’s interesting to note that, from the Romans until the mid- sixteenth century poetry has few, if any, positive scenes of ice and snow, happiness and joy is always found indoors, in the Anglo Saxon mead hall, or safe at the Elizabethan fire side, away from the elements and dangers of outside in winter.

Chaucer begins his prologue with an April shower and a description of  spring¹. Shakespeare references all seasons – it’s impossible to capture his use of weather in anything less than a whole book – and has some stunning storms too. His weather is used as portent, reflection of the central character’s tumult or as plot devices ( ‘Macbeth‘, ‘Lear‘, ‘The Tempest‘ ). But John Donne is an indoor poet ‘Busy old fool, unruly Sun’² castigates the daylight for breaking in upon a pair of lovers.

spring¹. Shakespeare references all seasons – it’s impossible to capture his use of weather in anything less than a whole book – and has some stunning storms too. His weather is used as portent, reflection of the central character’s tumult or as plot devices ( ‘Macbeth‘, ‘Lear‘, ‘The Tempest‘ ). But John Donne is an indoor poet ‘Busy old fool, unruly Sun’² castigates the daylight for breaking in upon a pair of lovers.

Pope is wonderfully practical about weather, satirising those gentlemen  and women who built their grand homes in the new Italianate Palladian style, which was better suited to the climate of the southern Mediterranean than those of these northern isles³. As is Austen, in ‘Northhangar Abbey‘ Catherine Morland doesn’t feel herself to be in an abbey at all, until she has spent a gale-swept night hearing slamming doors and ghostly howling along passage ways.

and women who built their grand homes in the new Italianate Palladian style, which was better suited to the climate of the southern Mediterranean than those of these northern isles³. As is Austen, in ‘Northhangar Abbey‘ Catherine Morland doesn’t feel herself to be in an abbey at all, until she has spent a gale-swept night hearing slamming doors and ghostly howling along passage ways.

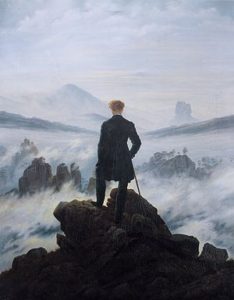

It is the romantics who really embrace the idea of weather; weather as manifestation of Pantheistic nature (Wordsworth), its extremities as  inspiration (Coleridge), as external reflection of self, or internalised (Shelley and Keats, respectively). Then as high passion in the Brontes, whose characters define themselves by the weather (think of Cathy and Heathcliff in’Wuthering Heights‘).

inspiration (Coleridge), as external reflection of self, or internalised (Shelley and Keats, respectively). Then as high passion in the Brontes, whose characters define themselves by the weather (think of Cathy and Heathcliff in’Wuthering Heights‘).

Through Clare, Hardy, Dickens, Ruskin and Woolf, up to modern times, Harris journeys through the letters, art and lives of English writers and artists ( Constable and Turner are included, as is Atkinson Grimshaw and David Hockney, all artists who were intrigued by weather, though the classic romantic painting above is by a German, Friedrich ). Woolf’s eponymous character, ‘Orlando‘, is often Harris’s touchstone for each age, finding, in the modern one, that Victorian gloom has quite dissipated.

by William Hilton, oil on canvas, 1820

Erudite and sympathetic, Harris treats us to telling detail as well as the grand movement. She distinguishes between those who observe and enter into the weather by choice and those who, perforce, understand its ways – John Clare (left) was the son of a farm labourer, Constable spent a year as a miller’s apprentice. It’s intriguing to see just how much, and how differently, English weather has influenced and inspired its writers

An interesting and entertaining read and, at a well-organised, close packed 417 pages, including notes, a book which can be dipped into as well as read from cover to cover. One for the Christmas stocking perhaps?

¹’The Canterbury Tales‘

²’The Sun Rising‘

³His followers of fashion were ‘Proud to catch cold at a Venetian door.’ Epistle to Lord Burlington

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy Novels Historical Landscape

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts