The recent post ( A Child’s Eye ) sent me back to two books which I read some time ago and which I have now thoroughly enjoyed re-reading. Both of them treat events of childhood, as seen through the eyes of a child, which resonate far into adulthood. Both are densely plotted, beautifully written and yet easy to read.

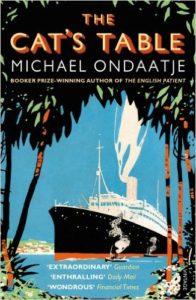

The first, Arundhati Roy’s ‘The God of Small Things‘ (Harper Collins, 1997) was the Booker prize winner almost twenty years ago and, I suspect, many people reading this post will have read it when it was first published. The second ‘The Cat’s Table‘ by Michael Ondaatje (Vintage, 2012 ) is more recent and less garlanded (though Ondaatje won the Booker with ‘The English Patient‘). Both books deal, at least in part, with a post colonial society and the relationship of its inhabitants with both the idea and the fact of the departed colonisers, but that is not the centre of either of these stories.

The first, Arundhati Roy’s ‘The God of Small Things‘ (Harper Collins, 1997) was the Booker prize winner almost twenty years ago and, I suspect, many people reading this post will have read it when it was first published. The second ‘The Cat’s Table‘ by Michael Ondaatje (Vintage, 2012 ) is more recent and less garlanded (though Ondaatje won the Booker with ‘The English Patient‘). Both books deal, at least in part, with a post colonial society and the relationship of its inhabitants with both the idea and the fact of the departed colonisers, but that is not the centre of either of these stories.

Roy’s, her debut novel, is set, mainly, in steamy Ayemenum, Kerala, southern India, but documents the seminal events in the lives of twins, Esthappen and Rahel ‘two egg twins‘. It moves about in time, beginning with Rahel’s return to the family home but reaching back to her childhood and the events of 1969.

The world of 1960s Kerala, as well as the family’s history, are beautifully captured from the point of view of the twins, though not in the first person. But their experiences are made immediate by the prose, words which seem to spring from the mind and the eye of the child and catch the innocence and the darknesses at the edge of childhood.

Ondaatje’s book is set on board a passenger steamship and charts the  languid three-week journey from Colombo, Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) to Britain, made by eleven year old Micheal in 1954. Ondaatje has said that it was inspired by just such a journey which he made as a young child. The ‘Cat’s Table’ in question, Table 76, is the table in the dining room most distant from the Captain’s table, the lowest down the social scale and it is populated by an intriguing ragtag of people.

languid three-week journey from Colombo, Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) to Britain, made by eleven year old Micheal in 1954. Ondaatje has said that it was inspired by just such a journey which he made as a young child. The ‘Cat’s Table’ in question, Table 76, is the table in the dining room most distant from the Captain’s table, the lowest down the social scale and it is populated by an intriguing ragtag of people.

It too speaks of childhood, in the adult Michael’s voice, showing the social bounds of what was permitted and what was not, the hardness of an unloved child and his intelligence in knowing what he can get away with. There are the small triumphs and disasters of burgeoning friendship with ‘quiet Ramadhin’ and ‘exuberant Cassius’ in the close confines of the ship and his relationship with cousin Emily, his ‘machang‘ whose father was a punisher. Ondaatje’s prose shimmers, perhaps with fewer pyrotechnics than Roy’s, but with the same, dreamlike quality.

Both books have a mystery at their centre, which is seeded in the reader’s mind early on, but the events of which only gradually become apparent. In the Roy it is two deaths, in the Ondaatje a prisoner and both books show the impact of those events upon their protagonists in later life. An excellent pair.

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy Landmarks Novels Historical Short Stories Vive la Revolution! Summer Reading in Autumn

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts