…is the title of a new exhibition at Tate Britain (Pimlico tube station, Victoria Line). It is well worth a visit, as the reviews suggest. I went yesterday and found it interesting and thought-provoking. It seeks to explore ways in which Empire shaped practices and themes in British, and other countries’, art, from the early colonial period until the present day.

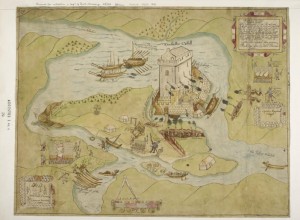

In part, the exhibition documents the artistic narrative in Britain. From the earliest British map-making of exploration across the globe, progressing  through the scientific collecting of new species of plant and animal in drawings and paintings, to the collections of glamorous curiosities (and real engagement with new peoples and cultures). The eulogizing of empire and its representatives in classical ‘history paintings’ is shown, including attempts to show those colonised as ‘happy’ (presumably as colonial actions and the very act of colonising was questioned), as is anti-imperial art in Britain. By the way, I don’t see these phases as purely chronological, but rather strands which weave together in history, although some are stronger at certain times and some are almost impossible at other times. The difficulty of love or friendship between coloniser and colonised, when the balance of power in such a relationship is so unequal, has formed the subject matter of much literature from Forster to Rushdie.

through the scientific collecting of new species of plant and animal in drawings and paintings, to the collections of glamorous curiosities (and real engagement with new peoples and cultures). The eulogizing of empire and its representatives in classical ‘history paintings’ is shown, including attempts to show those colonised as ‘happy’ (presumably as colonial actions and the very act of colonising was questioned), as is anti-imperial art in Britain. By the way, I don’t see these phases as purely chronological, but rather strands which weave together in history, although some are stronger at certain times and some are almost impossible at other times. The difficulty of love or friendship between coloniser and colonised, when the balance of power in such a relationship is so unequal, has formed the subject matter of much literature from Forster to Rushdie.

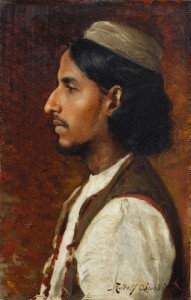

The exhibition also seeks to document how the other side of the equation worked in artistic terms. How indigenous civilisations responded, first to the explorers and those of genuine curiosity, then to the trade and profit-driven imperial expansion, then, once empire receded, to its legacy. This second aim is, necessarily, less supported by works of art than the former, but some of the most interesting pieces in the whole exhibition were those from Indian, African, native American or Antipodean Aborigine artists.

I was disappointed to find that there were no postcards or other images of the wonderful early twentieth century Asafo (West African) banners hanging in Room 1, Mapping & Marking. The banners take the same form as regimental colours and each incorporates, somewhere within its design, a Union flag – the Asafo were allies of the British. But the main elements of the designs were of the Asafo’s allies, as portrayed through the filter of Asafo artistic tradition, a tradition of design based upon depictions of the natural world. So, a pilot is shown in a vehicle which resembles a fish more than it resembles an early bi-plane and artillery is shown as a fire-breathing serpent. In Room 2, Trophies of Empire, there are exquisite artefacts from the indian sub-continent (I covet the intricate ivory chess set) and fine, bold sculptures from Nigeria and Polynesia, so influential on twentieth century western art. A figure by Eric Gill sits next to that by an unknown Nigerian sculptor, just to demonstrate that influence.

The dates of some of the works surprised me. A seventeenth century British traveller depicted in silk pyjamas with an Indian boy attendant, for example and the exhibition includes Sir Francis Drake and his contemporaries, and Ireland as empire. These are earlier than I think of, when I think of ’empire’, approximately from Woolf to Victoria, but that’s wrong, it stretches back much further. A portrait of an Elizabethan gentlemen, in usual ruff and silk finery, but completely bare-legged, out of respect to his Irish foot-soldier troops, was a bit jolting. Room 4 – ‘Power dressing’ has its share of colonising grandees who adopted ‘native’ garb and indigenous great and good adopting western dress.

Room 3 – Imperial Heroics has a good collection of history paintings, some of which were famous from the day they were first exhibited, like ‘The Death of Woolf’. (Incidentally, I recommend Simon Schama’s little-known not quite history, not quite fiction, story about Benjamin West, its artist, called ‘In Command’.) Others, like ‘The Death of General Gordon’ inspired Hollywood (no, Gordon does not look like Charlton Heston, though both ‘pictures’ show them standing atop some stone steps before the rampaging followers of the Mahdi). This exhibition encourages such lateral thinking.

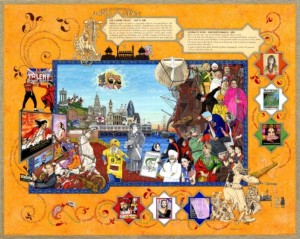

The final rooms contain artworks by those artists from former colonies who travelled to Britain post  WWII to study and work, usually in London. And, to bring us completely up to date, a 21st century version of the old ‘Imperial Federation’ Map of the World (the British Empire in pink) and a wonderful Singh twins collage entitled ‘EnTWINed’.

WWII to study and work, usually in London. And, to bring us completely up to date, a 21st century version of the old ‘Imperial Federation’ Map of the World (the British Empire in pink) and a wonderful Singh twins collage entitled ‘EnTWINed’.

The exhibition runs until 10th April 2016 and costs £16 (concessions available).

If you enjoyed reading this post you may also enjoy Frank Auerbach Barbara Hepworth Eric Ravilious or any of the other posts on exhibitions to be found in ‘Worth a Visit’ or ‘London’ tags.

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts

2 responses to “Artist and Empire”