Most writers will tell you that the only way to really learn how to write well and to keep on improving, is to write, then write some more and then write again. I have blogged before about the range of writing courses currently available ( see Help & Self-help ), but, however good these are, they cannot replace the activity itself.

Most writers will tell you that the only way to really learn how to write well and to keep on improving, is to write, then write some more and then write again. I have blogged before about the range of writing courses currently available ( see Help & Self-help ), but, however good these are, they cannot replace the activity itself.

I am now writing my third book of fiction ( not counting the shorter versions of ‘The Village‘ or the short stories included in the 2015 ‘Compendium‘ ). I’ve learned a lot from writing the other two. Sometimes it’s necessary to make mistakes in order to get to  where you want to be and, though I am nowhere near my final destination, I can already look back along the path which I have travelled and see lessons learned.

where you want to be and, though I am nowhere near my final destination, I can already look back along the path which I have travelled and see lessons learned.

I also begin to see how being a writer is affecting my every day life. Not just in terms of my writing related activities, like promoting books, helping organise a Literary festival and speaking regularly with other writers, but in my non-writing related activities too. Like, er, watching TV.

Imagine the lamp-lit room, two people sit on a sofa, transfixed by the moving pictures. They are watching the final episode of the nail-biting, thirteen episode thriller series, in which the killer is revealed. My husband sighs and smiles. I am unimpressed. ‘Of course it was him, didn’t you spot that in episode two?’ I say. My husband ( an intelligent fellow and no mean cineaste ) looks at me perplexed. No, he didn’t. Odd, I think, wasn’t he watching attentively?

A few days later I speak about the series denouement with a friend, also a writer, and I tell her about this. ‘Don’t blame him,’ she says. ‘Most people wouldn’t spot it. You only saw it because you plot all the time.’ Apparently it happens in her household too. It’s the writing of plots that does it.

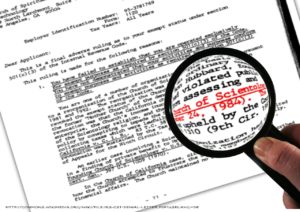

Now, I’m not talking about actual ‘clues’ here, the information provided by the writer to the reader or viewer, often obliquely, which should enable the reader or viewer to formulate their own ideas about the denouement. These, ‘the dog in the night time‘* clues, are most evident in detective fiction and perhaps most of all in the Agatha Christie ‘country house’ type mystery ( though they don’t just happen in country houses – any enclosed community will do – like the monastery in ‘The Name of the Rose‘ for instance ).

They are part of the relationship between writer and reader and some aficionados of detective stories won’t read books which aren’t what they regard as ‘honest’ i.e. that give the reader an adequate amount of information, albeit sometimes in obscure ways, to allow them to logically derive the ‘answer’. Their enj oyment in the book is partly one of solving an intellectual puzzle.

oyment in the book is partly one of solving an intellectual puzzle.

Unsurprisingly writers tried to formulate their own ‘rules’ for such books. Take a look at the ‘Decalogue’ of Ronald Knox, a member, with Christie and others, of the 1920s ‘Detection Club’, for a wonderful example of these rules and how they echo their period. Knox himself is a very interesting character, a Catholic priest and translator of the Bible, as well as a writer of detective fiction, his radio broadcast of fake revolution in 1926 London ‘Broadcasting from the Barricades‘ prompted minor panic and inspired Orson Welles’ more famous ‘The War of the Worlds‘ radio broadcast.

But no, ‘clues’ aren’t what I’m referring to. Rather it is an element in the fabric of the story, an enabler or marker, which will lead, inexorably, to the denouement. That’s what it’s there for, disguised in  background colour or hidden in a piece of character revealing dialogue, but its purpose is to facilitate the ending, it’s part of the plot. And once you spot it, you start seeing others and the ending just follows.

background colour or hidden in a piece of character revealing dialogue, but its purpose is to facilitate the ending, it’s part of the plot. And once you spot it, you start seeing others and the ending just follows.

So never watch drama on TV with a writer, unless you can avoid it, or she can keep schtum.

*One of the most famous quotations, used in lots of places since, is from ‘Silver Blaze‘ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts