This year’s winner of the Man Booker Prize is a startling and engrossing read. It’s astonishing that it’s George Saunders first novel. I haven’t read his short stories, though he was on my radar as a hugely skilled writer and someone I knew I should read. I certainly will now. So, what to say about this complex, multi-layered and unusual book?

This year’s winner of the Man Booker Prize is a startling and engrossing read. It’s astonishing that it’s George Saunders first novel. I haven’t read his short stories, though he was on my radar as a hugely skilled writer and someone I knew I should read. I certainly will now. So, what to say about this complex, multi-layered and unusual book?

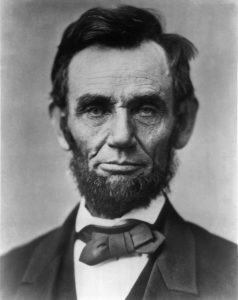

First, the title. Saunders is a Buddhist and, in Tibetan Buddhism a bardo is a place of transition, between life and re-birth, between waking and sleeping, between dreams and reality. The Lincoln in this place is Willie, 11 year-old son of Abraham, who died in February 1862 after a fever. It is the height of the American Civil War and one of the first of those truly awful battles with massive lists of dead, at Fort Donelson, is taking place (indeed we meet a casualty, briefly, in the bardo who describes the battle and its freezing aftermath ). The Union ‘won’, (their first clear-cut major battle victory) but the death toll on both sides was very high, something which was to become a feature of this, the first semi-mechanised war. So this is a time of death and mourning, a dark time in the nation, as well in Abraham Lincoln’s family life.

The ‘action’ takes place over one night, the night after Willie’s internment, when his father paid a visit to the cemetery where his son lay to  mourn him privately. This real occasion is the driver of the plot. But before the President’s arrival we are introduced to a collection of spirits who linger in that cemetery, their own burial-place. Many of the inhabitants of this little post-life community are either ignorant of, or unwilling to admit to, their having died, though they have to make an effort to stay there, to resist the call to another place.

mourn him privately. This real occasion is the driver of the plot. But before the President’s arrival we are introduced to a collection of spirits who linger in that cemetery, their own burial-place. Many of the inhabitants of this little post-life community are either ignorant of, or unwilling to admit to, their having died, though they have to make an effort to stay there, to resist the call to another place.

The spirits are the book’s many narrators, their polyphonic voices describing events. They are often untrustworthy, but always have distinctive voices. Some lived lives neither evil nor saintly, others are innocents abused, yet others killers and abusers. Indeed, there seems a preponderance of the negative, the uncharitable, the weak-willed or prejudiced, though we are told that the effort needed to maintain themselves in that place drowns out sympathy and softer virtues. The story is told, with amazing virtuosity, in dialogue between these characters, their interior monologues, or through excerpts from the writings of eye witnesses, subsequent memoirs or contemporary newspaper reports (real or fictional).

The bardo may be a Buddhist concept, but the place of the novel owes much to purgatory, particular Dante’s, as the spirits already exhibit ‘disabilities’ relating, to a greater or lesser extent, to their sins in life. So, a rich miser gravitates horizontally, his head pointing like a compass needle towards  whichever of his many properties is worrying him at the time. Some of these grotesqueries are amusing – the lustful, but kindly and gentle Vollman walks around with a super-engorged member; some are cruel – the inability to speak of the slave girl raped repeatedly, whose calls for justice were ignored in life. Many are bawdy.

whichever of his many properties is worrying him at the time. Some of these grotesqueries are amusing – the lustful, but kindly and gentle Vollman walks around with a super-engorged member; some are cruel – the inability to speak of the slave girl raped repeatedly, whose calls for justice were ignored in life. Many are bawdy.

Lincoln is living through a purgatory of his own. As the bereaved and anguish parent, but also as the President who must order others’ sons to die. It is as they watch and experience his torment (through ‘joining with’ the President) that our main narrators, Vollman and Bevins, regain their empathy and kindness, which eventually leads them to decide to ‘go on’ to another place. Thus the ‘better angels’ of their nature triumph ( and there is a reference to this most oft-quoted Lincoln line from the Gettysburg address ).

This is a magnificent and very clever book, which is profoundly humane. All, or most of, human life is there and the ‘war’ for Willie’s soul is also a war between the best and the worst in us. Kindness and sympathy wins, at cost and risk – the spirits do not know what it is that they go on to, Lincoln resolves to go on with the terrible sacrifice to reach a better ending, not really knowing what that ending might be. The writing, capturing so many, disparate voices is a tour de force. I will, I think, come back to this book again and again.

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy others about books Novels Historical Two Novels Historical Naval Novels

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts

2 responses to “Lincoln in the Bardo”