Lapidary (n) an artisan who forms stones, minerals or gemstones in decorative or commemorative items.

So to the Musee Lapidaire, one of the seven sites included on the Pass Plein for Narbonne ( 15 euros per person ). Not, perhaps, a visitor’s first choice, that would be the Archbishop’s Palace complex, with the  Archeological Museum and Cathedral, all in the very centre of town ( of which more later ). But, hey, after an excellent lunch in Les Halles food market ( see left ) and it being just around the corner, why not?

Archeological Museum and Cathedral, all in the very centre of town ( of which more later ). But, hey, after an excellent lunch in Les Halles food market ( see left ) and it being just around the corner, why not?

But where was it, this ‘Stone Museum’? We circle what looks like an abandoned gothic church, a plaque on its wall recounting that it was sacked by revolutionaries in the 1790s. Its door proclaims that the museum is within, but it’s closed.

Anyone for a coffee? There’s a little PMU cafe nearby and the museum opens in twenty minutes. Shall we bother – isn’t it just a pile of stones? Oh well, coffee would be good anyway.

Half an hour later and we return. The doors are open and we present our passes to the lady on the desk, who directs use through a set of doors. The church, Notre-Dame de Lamourguier, has been stripped back to its bare walls, its glass windows plain, not coloured and with few of its original 13th century embellishments ( except one beautifully carved balcony ) still in place.

Inside, stones. Rows and rows of stones.

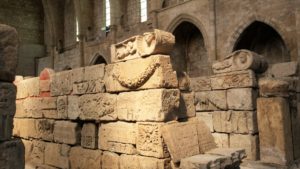

From the vantage point of the doors one looks down on a sloping walkway flanked by ‘wall’ of stones  stacked upon each other, ten to twelve feet high. Bas reliefs, grave stele, columns and statues, sarcophagi and tombs. All were found locally, many from the 16th century walls of Narbonne when they were demolished in the late 19th century to allow the town to grow. Mostly Roman, dating back to the first century CE, there are over 2,000 blocks, statues and tombs deposited in the church.

stacked upon each other, ten to twelve feet high. Bas reliefs, grave stele, columns and statues, sarcophagi and tombs. All were found locally, many from the 16th century walls of Narbonne when they were demolished in the late 19th century to allow the town to grow. Mostly Roman, dating back to the first century CE, there are over 2,000 blocks, statues and tombs deposited in the church.

The first impression is one of uniformity. The stones are, roughly, the same soft whitish grey, marble or granite and, though piled on top of one another, reach a uniform height. Within these ‘walls’ there are large blocks and small ones, extended friezes of carved cherubs, drapery and cornucopia and many inscribed stones. The grave stele of Manius Egnatius Lugius, cook, includes carvings of a cleaver and long-handled filleting knife. There are busts and sculptures and a preponderance of bull’s heads – the Cult of Cybele and its associated Torraria was very strong in first century Narbo Martius.

The initial path through the stones meets a cross roads, there are side paths leading to the church’s side-chapels, which contain the upright statuary and the whole sarcophagi ( including metal linings ). Everywhere there are names and professions, (there are five tonsors or barbers, for example) and little messages amongst the decoration.

The initial path through the stones meets a cross roads, there are side paths leading to the church’s side-chapels, which contain the upright statuary and the whole sarcophagi ( including metal linings ). Everywhere there are names and professions, (there are five tonsors or barbers, for example) and little messages amongst the decoration.

After a while the place becomes magical, the visitor wanders, Alice-like, curious in a strange world. Just as in any cemetery, though without the actual remains of the dead, it draws the visitor into a time and place long gone, though with added poignancy and mystery, as many of these stone inscriptions are incomplete. It is also a monumental data store, weightier than any cloud ( and much more beautiful ).

The Musee Lapidaire is open this year, but the collection is due to be transferred to the Musee Regional de Narbonne Antique in 2017 and, though the church will remain open to the public, this unique and perfect placement will disappear. If you happen to be passing through Narbonne and have a couple of hours to spare, go and visit it before its gone.

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy El Palacio del Virrey de Laserna Undiscovered The Land of the Two Rivers The First Library

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts