The Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury is familiar to the modern art cogniscienti (though not to me). It was what its title suggests, a place for the doctoring of horses, built in 1797, originally as part of  the mews behind the Hotel Russell. Redeveloped in 1993 it is now an arts venue, specialising in the avant garde. On The Colonnade, just behind Russell Square tube station, it is an ‘industrial’ style brick building of two storeys, but the entrance leads you down a ramp (down which the horses would have been lead) to a large, semi-subterranean, cobbled-floored room which is now used as a cinema. On Thursday night it was the venue for a discussion between Jeremy Deller, Turner-prize winning artist and Scott King, whose solo show Welcome to Saxnot, I blogged about here.

the mews behind the Hotel Russell. Redeveloped in 1993 it is now an arts venue, specialising in the avant garde. On The Colonnade, just behind Russell Square tube station, it is an ‘industrial’ style brick building of two storeys, but the entrance leads you down a ramp (down which the horses would have been lead) to a large, semi-subterranean, cobbled-floored room which is now used as a cinema. On Thursday night it was the venue for a discussion between Jeremy Deller, Turner-prize winning artist and Scott King, whose solo show Welcome to Saxnot, I blogged about here.

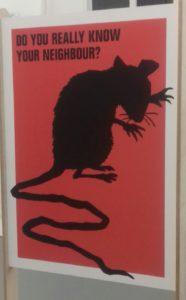

The room was full (the sign outside said that the event was sold out) and a copy of the Welcome to Saxnot brochure was found on every chair. Jeremy Deller introduced his friend and explained that their discussion was very much what they discussed in everyday life, down the pub, over a coffee, etc.. That evening would, however, centre on Scott’s recent show, which explored the nostalgic desire to live in a land of unanimity and safety, drawing on experiences, real or imagined, during WWII and the decades following, as typified by the popular Butlin’s holiday camps: and how that desire could be subverted into a much darker vision.

desire could be subverted into a much darker vision.

I was intrigued to find that King’s show had been conceived of, though in a different form, before the 2016 Referendum campaign and vote, based upon the artist’s own memories of Butlin’s holiday camp at Filey. Of working class stock, the artist has said that his father and others like him were exactly those aging northern voters who supported Brexit. He isn’t dismissive of this, just as he doesn’t dismiss the pleasures of Butlin’s for working people in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, rather he seeks to understand it and its impact. This is the background to the show and the evening’s conversation.

A series of slides accompanied the discussion. Butlin’s postcards featured, hyper-coloured and posed pictures of happy campers (all white, all of a clean-cut, aryan type) contrasted with impromptu photographs of the actual holiday camps (in part because these were in black and white). The real holidaymakers were clearly enjoying themselves though, albeit in a somewhat regimented way.  Interestingly, the man I sat next to told me that the colours of the Butlin’s postcards were very like those of Korean or Chinese ‘official’ postcards today.

Interestingly, the man I sat next to told me that the colours of the Butlin’s postcards were very like those of Korean or Chinese ‘official’ postcards today.

There were also Ministry of Information and news photographs of London during the blitz – of destruction and desolation, but also of plucky EastEnders making tea in the underground station bomb shelters and singing songs. These were also posed and lit. Yet Mass Observation diaries show that this jolly, inclusive experience was not universally shared – the deep shelters were generally unpleasant, over-crowded, smelly and lacking any privacy, something to be endured rather than enjoyed.

Welcome to Saxnot is very strong on propaganda, all the Britlin’s material and some of the stand-alone artworks are, more or less, propagandist. So I would have liked the speakers to explore this a bit more. It is interesting that war-time propaganda had already coloured the views of English people, even Londoners, by the time the epic documentary series, The World At War, was made in the 1980s. A clip showed elderly EastEnders recalling the jolly times they had had in the shelters, already  using phrases like ‘pulling together’ and ‘everyone in the same boat’. How far have these attitudes impacted upon their children and grandchildren? How far on Brexit? Only this week in the context of the Brexit negotiations, a German Minister suggested that the British might do better if they did not hark back to WWII all the time (now almost three-quarters of a century ago).

using phrases like ‘pulling together’ and ‘everyone in the same boat’. How far have these attitudes impacted upon their children and grandchildren? How far on Brexit? Only this week in the context of the Brexit negotiations, a German Minister suggested that the British might do better if they did not hark back to WWII all the time (now almost three-quarters of a century ago).

The conversation and slides also touched on the dissolution of old certainties. The traditionally defined ‘working class’ disappeared and assets formerly held for the good of all were sold off – council housing, utilities, transport systems. The ‘communal’ became derided and second class. There are probably sociological and ‘state of the nation’ texts which document this and seek to explore its psychological impact, it is recent history after all. Thursday’s conversation simply didn’t last long enough to get into any more detail and that was not, anyway, its purpose. It closed with the decline of Butlin’s in the 80s and 90s and some truly grim photographs of crumbling cabins and enforced gaiety, before the discussion was opened up to questions from the audience.

I thoroughly enjoyed listening and watching, though I wanted more depth and exploration. Like so much that is good and insightful, Welcome to Saxnot and this conversational continuation of it, prompts consideration of the recent past which seems obvious once the thought’s been had, but might not have come about without the artwork in the first place.

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also enjoy Rachel Whiteread Rainbow Aphorisms East End Vernacular Referendum II – The Hero Returns The Demagogue’s Dictionary

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts