Rachel Whiteread is one of a handful of modern British artists whose name is known beyond the modern-art loving  population, to the wider general public.

population, to the wider general public.

British enthusiasm for modern and/or conceptual art has definitely increased in the early years of the 21st century, with Tate Modern now the third most visited site in the capital ( behind the British Museum and the National Gallery ). The Royal Academy’s 1997 Sensation exhibition of Young British Artists brought names like Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Whiteread to public notice at the same time as the YBAs were being entertained in Downing Street. The tone of the publicity attaching to the annual Turner Prize has moved from confected outrage to coverage of a topic of general interest and TV regularly does programmes on the candidates. That is not to say that there aren’t plenty of people for whom art is a landscape or portrait and its merit judged by purely representational standards, just that this is no longer the exclusive norm.

Tate Britain is currently showing a major Whiteread retrospective including sculpture and some drawings from three decades of work. It ends on 21st January, so this is your last chance to see it.

I confess that Whiteread is not my favourite modern artist working today. Nonetheless I respect her artistic endeavour and integrity and I find the idea of reproducing space, as opposed to solid matter, an intriguing one.

This exhibition has many excellent examples of works which do this. The famous Torso casts, in different materials, of the insides of hot water bottles, or the elegant Untitled (One Hundred Spaces) in the Duveen Gallery (South) which  comprises 100 different coloured casts of the space beneath the underside of found chairs, arranged in a five by twenty formation. There is Untitled (Room 101) a plaster cast taken inside the room in Broadcasting House where George Orwell worked during WWII and which is said to have inspired Room 101 in 1984. This recording studio no longer exists so Whiteread’s cast of the space within it is all that remains.

comprises 100 different coloured casts of the space beneath the underside of found chairs, arranged in a five by twenty formation. There is Untitled (Room 101) a plaster cast taken inside the room in Broadcasting House where George Orwell worked during WWII and which is said to have inspired Room 101 in 1984. This recording studio no longer exists so Whiteread’s cast of the space within it is all that remains.

Other large pieces include Untitled (Stairs) 2001, a cast of the stairs in an old East London synagogue (eventually the artist’s home) which captures the  wear and tear on the treads, the scratches and chips which evidence daily use over the centuries. Outside, on the Tate lawn is Chicken Shed 2017, the latest in her series of Shy Sculptures, in which she places casts of unassuming domestic buildings like huts and sheds in remote or unusual locations.

wear and tear on the treads, the scratches and chips which evidence daily use over the centuries. Outside, on the Tate lawn is Chicken Shed 2017, the latest in her series of Shy Sculptures, in which she places casts of unassuming domestic buildings like huts and sheds in remote or unusual locations.

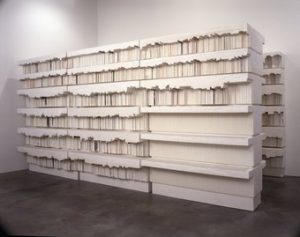

My particular favourite, however, was the plaster bookshelves, which were created as part of preparation for the Holocaust Memorial in Vienna. These catch the form of the space around the books, delineated by the varying indentations into that space signifying the height and thickness of each book, ( although the exhibition leaflet suggests that the books are also represented on the shelves, just with their spines facing inwards and their page ends showing ). Perhaps it’s both? Regardless, it makes one think about the physical matter of books and bookshelves and, by implication, their contents ( even if invisible ). Which is why, I guess, Whiteread chose the structure of an impenetrable library for the Memorial. To represent all that was within and is now lost.

The Rachel Whiteread exhibition is on at Tate Britain until 21st January. It costs £15 to enter, concessions available.

If you enjoyed reading this article and would like to read more about modern art try Welcome to Saxnot Rainbow Aphorisms Vittorio Scarpati & Cookie Mueller Carol Robertson – Stars at Flowers

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts