The New York Subway has its escaped alligators (the descendants, supposedly, of those creatures once fashionable as up-market pets and flushed down the lavatory when they became too tiresome or their rich owners got bored); Warsaw has its armed resistance fighters ( Wadja’s Kanal was such  a great film ); Paris has Leroux’ Operatic phantom escaping through the catacombs ( used by communards and revolutionaries and appearing most recently in the BBC series Black Earth Rising ), likewise Rome with its ancient Roman and early Christian sites (as featured in early Christian writings and in almost anything by Fellini). In Vienna, fingers reach through a pavement grill in a cobbled street to the sound of a zither after a pursuit through the sewers, from The Third Man, of course, by Graham Greene.

a great film ); Paris has Leroux’ Operatic phantom escaping through the catacombs ( used by communards and revolutionaries and appearing most recently in the BBC series Black Earth Rising ), likewise Rome with its ancient Roman and early Christian sites (as featured in early Christian writings and in almost anything by Fellini). In Vienna, fingers reach through a pavement grill in a cobbled street to the sound of a zither after a pursuit through the sewers, from The Third Man, of course, by Graham Greene.

All these cities have their subterranean tales, mythic, fictional or based in reality. But London?

The closest, I would guess, are stories of the London Underground tunnels becoming air raid shelters in WWII ( see Make Do and Mend ). Although apparently smelly and unpleasant, with no privacy, the deep tunnels were, at least, safe and spawned nostalgic ‘recollections’ actively encouraged during and after the war by the Ministry of Information.

London under ground fares somewhat better as regards movies and TV, though mostly of the ‘horror’ variety – The Death Line (1972), Quatermass and the Pit (1959) the latter being cited by Stephen King and John Carpenter as being influential on their own work and giving rise to a subsequent film. I recall any number of Dr Who episodes from childhood in which London Underground is the haunt of monsters, or a safe haven from the ravaged city above. it was a cheap location to film in I suppose.

London under ground fares somewhat better as regards movies and TV, though mostly of the ‘horror’ variety – The Death Line (1972), Quatermass and the Pit (1959) the latter being cited by Stephen King and John Carpenter as being influential on their own work and giving rise to a subsequent film. I recall any number of Dr Who episodes from childhood in which London Underground is the haunt of monsters, or a safe haven from the ravaged city above. it was a cheap location to film in I suppose.

Again, however, London is eclipsed by the NY Subway, the scene for so many movies – The Taking of Pelham 123, twice, Die Hard with a Vengeance, Walter Hill’s The Warriors, ( based on Herodotus’ Anabasis ), Jules Dassin’s The Naked City with its climax on the Williamsburg Bridge. But Orson Wells as Harry Lime being pursued by British army officer Trevor Howard and US author Joseph Cotton through Vienna’s sewers at the climax of Carol Reid’s wonderful film is pretty unbeatable.

Yet, in Paris, where Paris Underground (1945) wasn’t actually about the Metro, the gendarmerie accidentally discovered in 2004 an entire secret cinema in the Paris catacombs, beneath the Palais de Chaillot, complete with screen, projecting equipment, films, seats, fully functioning bar and restaurant. Even today no one knows who put it there. A wonderful example of the phrase ‘underground cinema’ becoming literal.

Parts of London Underground do better than others. John Betjeman celebrated Metroland and there is Julian Barnes’ novel of the same name, though this isn’t about the underground. Also Seamus Heaney’s District and Circle (Faber, 2006), though again the title is something of a metaphor, though Heany knew these tube lines well from his time in London. Peter Ackroyd’s novels are set in London though they have not, to my knowledge, explored the subterranean city, though his non-fiction London Under ( Vintage, 2012) takes a good look below the surface, as do any number of guides.

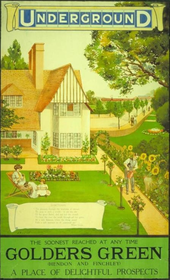

Art is well represented, especially on the newer lines, because of the visionary Frank Pick who employed the best graphic artists of the day to design the tilework and posters in the stations ( see Edward Bawden and, more recently, Rainbow Aphorisms ), but that’s for another piece entirely.

For more on London and its literature try London Books Common Books

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts