Thriller (n) – a novel, play or film with an exciting plot, typically involving crime or espionage. Long before Michael Jackson.

So what makes a good thriller? Jeopardy, tension, anxiety and anticipation, all designed to elicit suspenseful excitement in the reader and, of course, the desire to read on. Best-selling thriller writer James Patterson says thrillers are marked by “the intensity of emotions they create, particularly those of apprehension and exhilaration, of excitement and breathlessness, all designed to generate that all-important thrill.”¹

This can apply to the ‘classic’ type of adventure story, from Dumas and Robert Louis Stevenson onwards, with its cliff-hangers, set piece conflicts and imminent perils – usually with a relatively clearly defined hero and a dastardly villain (there’s nothing like a dastardly villain). I side with Nabokov here, who said he hoped that “the wicked but romantic fellow will escape scot-free and the good but dull chap will be finally snubbed by the moody heroine”² but acknowledged, tongue in cheek, that this wasn’t likely in the English tradition. I’m not so sure that’s the case any more.

Complex characterisation wasn’t really what these stories were about and yet they held the reader, largely because of their strong narrative drive and imaginative plots full of surprises. They often had exotic settings, a Treasure Island, or elements of the supernatural, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stephen King owes a lot to this tradition, as does Dan Brown. It harks back to the oldest type of story, be it Beowulf or Odyssey.

Complex characterisation wasn’t really what these stories were about and yet they held the reader, largely because of their strong narrative drive and imaginative plots full of surprises. They often had exotic settings, a Treasure Island, or elements of the supernatural, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stephen King owes a lot to this tradition, as does Dan Brown. It harks back to the oldest type of story, be it Beowulf or Odyssey.

Modern variants are legion. Add an appellation – crime, mystery or spy – to ‘thriller’. They range from the simple, not to say simplistic (a mixture of conspiracy, a mystery or crime, violence, sex, more action, sex (possibly kinky), a chase, danger, denouement – don’t knock this, it sells, ask the aforementioned Mr Brown) to the highly complex, with confusing motivations and allegiances, exploration  of character, truth and moral dilemmas – John Le Carré and Graham Greene are modern ‘literary’ exponents.

of character, truth and moral dilemmas – John Le Carré and Graham Greene are modern ‘literary’ exponents.

Thence to the ‘psychological’ thriller. So very popular, this has elements from the classic thriller – a situation of peril, building tension and plot twists, but with added human complexity, the suspense coming from a character’s inner conflict as well as her or his outward trials. Often involving secrets or events from the past catching up with protagonists, or a seemingly innocuous situation – a ride on a train, a lie casually told – turning into something far more threatening and dangerous. The way the tale is told may not be a standard third person narrative either, with the story told from different points of view or by an unreliable narrator. It adds to the complexity and the potential for mystery and surprise.

Many of today’s thriller writers are women and one, Val McDermid is on record as saying “Women are far more in tune with violence than men.” This isn’t the lurid focus on the tortured woman’s body which begins so many thriller novels or TV shows but a greater awareness, give 24 hour global news, of the real atrocities which real women are subject to right now. Does this awareness and understanding make women better writers of psychological thrillers?

Many of today’s thriller writers are women and one, Val McDermid is on record as saying “Women are far more in tune with violence than men.” This isn’t the lurid focus on the tortured woman’s body which begins so many thriller novels or TV shows but a greater awareness, give 24 hour global news, of the real atrocities which real women are subject to right now. Does this awareness and understanding make women better writers of psychological thrillers?

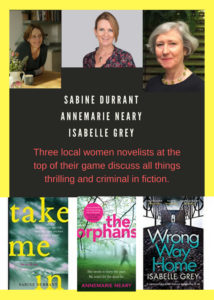

Come along to the Lambeth Country Show on 21st July and join the Clapham Book Festival discussion to find out. Thriller in the Park, with three top female writers of thriller fiction, two of whom their writing set in Lambeth. Who needs Hay when you’ve got south London?

¹Thriller (2006)

²Lectures on Russian Literature (1981)

For more about the Clapham Book Festival Clapham Book Festival 2018: How’d it go? Clapham Book Festival 2018: How’d we do? Crime and Punishment The Writing Game

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts