Tate Britain’s other Summer exhibition is Aftermath. Art in the Wake of World War One, which runs until 23rd September 2018.( See All Too Human for the other, now concluded )

The exhibition covers art in the immediate post war period and the 1920s across Britain, France and Germany, showing how artists reacted to the dreadful carnage and the economic consequences which followed. It begins with pictures of the trenches, bodies and ruins, like Paths of Glory by CRW Nevinson, or A Grave in a Trench by William Orpen (left). Both Orpen and Nevinson were official war artists but both fell foul of authority afterwards, when they tried to exhibit paintings thought to be too graphic or critical of the war by officialdom. A symbol common to artists from Britain, France and Germany was the abandoned soldier’s helmet, which features in a range of pictures.

carnage and the economic consequences which followed. It begins with pictures of the trenches, bodies and ruins, like Paths of Glory by CRW Nevinson, or A Grave in a Trench by William Orpen (left). Both Orpen and Nevinson were official war artists but both fell foul of authority afterwards, when they tried to exhibit paintings thought to be too graphic or critical of the war by officialdom. A symbol common to artists from Britain, France and Germany was the abandoned soldier’s helmet, which features in a range of pictures.

If you saw the Imperial War Museum’s excellent exhibition Truth & Memory, British Art of the First World War, in 2015, you will have seen many of the British paintings and sculptures in the early rooms, though not those from the continent and it’s interesting to see them displayed together.

There are significant differences too, between the attitudes of artists (and society) in Germany as compared with Britain and France. By November 1920 there were cenotaphs, tombs to the unknown soldier, in both Paris and  London, but the first national monument to commemorate the fallen in Germany was not built until 1931 (though many towns and cities commissioned memorials). Most memorials, from whatever nation, were deliberately abstract, so as to encompass ‘everyman’, though there were few memorials commemorating servicemen from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean. One such was that built to remember soldiers from India, the drawings for which are included in the exhibition . Incidentally Surrey County Cricket climb, hosts for the current cricket Test match between England and India are drawing attention to the contribution of Indian soldiers to WWI this very weekend.

London, but the first national monument to commemorate the fallen in Germany was not built until 1931 (though many towns and cities commissioned memorials). Most memorials, from whatever nation, were deliberately abstract, so as to encompass ‘everyman’, though there were few memorials commemorating servicemen from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean. One such was that built to remember soldiers from India, the drawings for which are included in the exhibition . Incidentally Surrey County Cricket climb, hosts for the current cricket Test match between England and India are drawing attention to the contribution of Indian soldiers to WWI this very weekend.

Attitudes towards disabled servicemen also differed and these are reflected in the art. In France disabled veterans featured prominently in public memorials, this continued well into the 1920s and they can be found in many painted scenes. In Germany the physically and psychologically damaged were often depicted in anti-war art, showing how those veterans were marginalised and mistreated by an increasingly unequal society. In Britain paintings and drawings of the disabled were considered only in a medical context (though sympathetic).

Attitudes towards disabled servicemen also differed and these are reflected in the art. In France disabled veterans featured prominently in public memorials, this continued well into the 1920s and they can be found in many painted scenes. In Germany the physically and psychologically damaged were often depicted in anti-war art, showing how those veterans were marginalised and mistreated by an increasingly unequal society. In Britain paintings and drawings of the disabled were considered only in a medical context (though sympathetic).

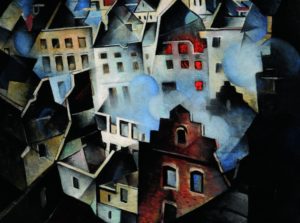

As time passed the art of the three countries went its own way, with German artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix, caught up in the social unrest of the 20s, while in France and Britain artists reached back to older traditions of pastoral, classical  and biblical painting. The profiteer became a staple figure in German new urban art, juxtaposed against the disabled veteran, with the worker was the new hero, while Bauhaus sought to shape the modern world. Meanwhile artists like Nevinson and Citroen were enraptured by New York, its dynamism and technology, at least initially.

and biblical painting. The profiteer became a staple figure in German new urban art, juxtaposed against the disabled veteran, with the worker was the new hero, while Bauhaus sought to shape the modern world. Meanwhile artists like Nevinson and Citroen were enraptured by New York, its dynamism and technology, at least initially.

This is an interesting and thought-provoking exhibition. It costs £18 per ticket (£17 concession) and is worth a visit. I particularly admired the series of simple woodcut-style prints of Kathe Kollwitz entitled War which I had not seen before. Amazing, powerful images of the impact of war on mothers and children. It’s worth going to this exhibition just to see these.

For more on art in 2018 in London try Frida Kahlo Edward Bawden Picasso 1932 Royal Art Rhythm & Reaction

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts